To start at the beginning of the story go here.

Rotella drove along the long green pitch that separated Mitnick’s house from the road, slowly curving towards the white steps that led up to the house. The statue of Athena was still out front, holding spear and shield as if calling ghostly legions to battle. Rotella parked in front of it.

Brick and Whip were waiting at the stairs. Brick as quiet as his namesake with Whip curling his lip in a familiar expression of contempt. I couldn’t help but smile at him, unable to resist the urge to egg him on, but also weirdly happy at being back on familiar territory.

Bulges under their sports jackets told me they were armed, but it was nice no one was waving a gun around. Stepping out of the car, I waited for Rotella to come around from the driver’s side before I said, “This is Inspecteur Rotella.” Unable to resist treating them like fools, I added, “The man Mitnick wants to meet.”

Whip’s mouth curled further in preparation for some insult, but Brick only gestured to Sophie as Rotella opened the door for her. As she uncurled herself from the automobile, Rotella said, “She is with me.” This statement caused me some perverse joy at the sensation of possessiveness it sparked.

Whip and Brick stared at us, evaluating the new and unexpected addition. After a moment, Rotella asked, “Does Mitnick wish to speak? Or no?”

Whip took control of the situation with a dismissive snicker and led the way up the stairs. Brick fell in behind us. We fell into line, reminding me very much of Capanne and its routines.

Through the big brass front doors, we were escorted past the antechamber fountain. The house showed no sign of the raucous party.

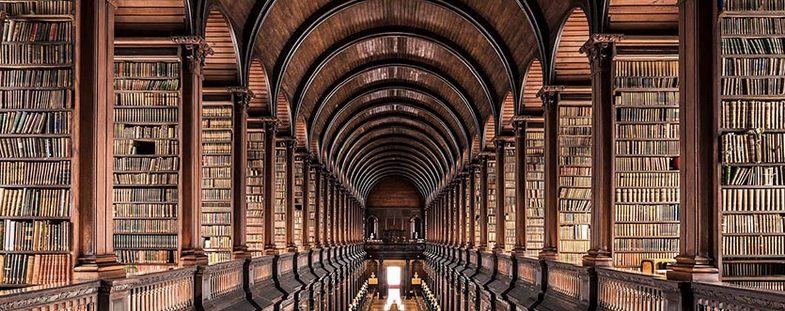

In the library, Mitnick sat behind his desk between his globe and his books, reading a newspaper with Cyrillic letters. At first we could only see the expensive brown shoes he had propped up on the desk. Then his big white smile came out from behind the paper, flashing in the room’s sedate light. He set aside his paper and gestured for us to enter. “Come in.”

I led the way, relieved to see there weren’t any of Mikhail’s vory in the room. “This is Inspecteur Rotella,” I told Mitnick as Brick and Whip positioned themselves behind us.

Mitnick’s gaze landed on Sophie. Looking like the statue of Athena had somehow become animated and walked into his house, she was impossible to ignore. Regardless of her resemblance to statuary, Mitnick showed his easy confidence. “And you are…?”

Sophie gave her name and nothing else. Mitnick nodded, immediately switching back to me and Rotella for further information.

“She is a professional friend,” Rotella answered.

As if she had disappeared, Mitnick extended his hand to Rotella with his usual warmth and grace. He gave Rotella’s reciprocating hand a single pump, his palms, I’m sure, being free from the sweat that began to cover mine. “It is good to meet you, Inspecteur. It gives me great pleasure knowing the city has such a competent officer watching over it.”

Rotella’s chuckle was more cynical than friendly, escaping him before the handshake was even complete. “Why would you think I was competent?”

Mitnick walked to the globe next to his desk. “I have heard many things,” he said. He touched the sphere and it glided open, revealing a bevy of crystal decanters filled with variously colored liquids. “From friends, you see. The city has many people that depend on you and your compatriots to keep them safe, yes?” Mitnick moved three glasses to this desk and took out a bottle that was filled with an amber liquid. “Politicians, developers, bankers. None of them could do business if they did not feel safe.”

“I mostly work in the outer banileue beyond the periphérique.” I don’t know why Rotella told this lie, but he did.

Mitnick knew as well as I did (I had told him, after all) that Rotella was investigating him, but he didn’t contradict the inspector. Instead, he poured liquor. “Ah, yes, the barbarians beyond our gates. No wonder you make the politicians feel safe, then.” He handed Rotella a glass and the other to me, and I felt it burn a hole in my hand. “Perhaps I should make a donation to the city, to better arm the gendarme that protect us from the insatiables.”

Rotella removed his sunglasses, carefully folding them up in his free hand and slipping them into his breast pocket. He stared openly at Mitnick, evaluating him and the Big Boss cliché that his actions were meant to evoke. It clearly wasn’t Rotella’s first time seeing someone put on this routine. “Will you not offer my companion something?”

Mitnick’s eyed Rotella as if he were on the other end of a chessboard. When the Inspector’s impassive expression didn’t change, he asked Sophie, “Would you like something? Some wine? Or perhaps champagne?”

The contempt Sophie harbored for Mitnick completely submerged beneath the smile she returned to him. “Champagne would be lovely.”

Mitnick gestured and I heard Brick’s heavy footfalls leave the room. Rotella sipped his liquor and also smiled at Mitnick, tinged with the scorn that the French reserve for people they have to remind of their manners. Sophie moved to one of the room’s sofas.

As Sophie left our orbit, Mitnick said to me, “You have done well to bring him.” He sipped his own drink, then said, “I do not believe the Inspector’s claims to incompetence.”

“Very kind,” Rotella responded, his tone absent of kindness.

“There is very little kindness in the house of Belarus,” replied Mitnick with as much honesty as I’d ever heard. “But there is patience. I have, as an example, been very patient with your snooping around me.”

Rotella was unmoved by the barb. “It is standard to investigate individuals that arrive with odd passports.” He gestured with his glass from Mitnick to his mahogany desk around to the finely crafted bookshelves with their leather-bound editions. “Particularly when they arrive with much cash.”

“Understandable. But the same men you protect, the bankers, developers, politicians, are the ones I befriend. And your investigation into my affairs makes them nervous. I need them to do business, you see.” Mitnick grinned. “So this means we need to do business.”

“If my snooping,” Rotella pronounced the words like flicking a bug off his sleeve, “finds that no one is acting out of order, business always proceeds. It is the way of things.”

“Ah, but this France, not Russia. Even the appearance of impropriety can make a politician here blush.” Mitnick continued to smile, but it became conspiratorial as he gestured slightly to Sophie. “Unless it involves the fairer sex, of course.”

Rotella nodded, acknowledging this reality. “True. Rumor, though, says your trouble involves the fairer sex.”

Mitnick leaned forward, joking amongst the boys. “I can assure you, Inspector, I am a happily married man.” From the background, Whip dutifully chuckled.

Rotella smiled mirthlessly, then drained his glass. Whatever was in it must have been good; he glanced with surprise into the cup’s emptiness, as if its quality had caused it to evaporate. Mitnick was prepared with a, “Would you like more?”

“Perhaps in a bit,” Rotella responded, sounding very much like a corrupt cop that was starting to loosen up. “But as you say, no one in my country cares what men and women do in their bedrooms. Unless, of course, someone is there against their will.”

Mitnick transformed his face into polite confusion, then glanced at me, pushing the unspoken question of, “Do you know what he’s talking about?” I shrugged. With this exchange complete Mitnick said, “I hold no one against their will.”

“But there are rumors,” Rotella persisted. “And these rumors make the men you desire the friendship of much more nervous than any snooping I may do.”

Mitnick’s imperturbable cool rippled as this statement landed, a barely detectable change in his exterior. “What rumors?”

To read the next chapter, go here.

To read the previous chapter, go here.

To read the author’s published work, go here.

Read More »